Solos Extr3mos, Choreographer and composer Billy Cowie. Performer: Luciana Croatto.

Solo Women also at home. Drawings projections: Silke Mansholt.

Solo From the Top of Tall Buildings. Voice: Clara García Fraile. Text: Billy Cowie.

Solo Restless Love. Voice: Elizabeth Woollett. Text: Goethe. Drawings and projection design: Silke Mansholt.

Lighting Design: Sebastián Viola, Mauricio Rinaldi. Costumes: Espacio Shera. Stage Manager: Lucía Banegas. Production in Argentina: Ladys González. Production Assistant: Lucía Ferré.

As I was watching this dance performance, several statements came to my mind that could serve as a prelude to the construction of a semiotics of the body.[1]

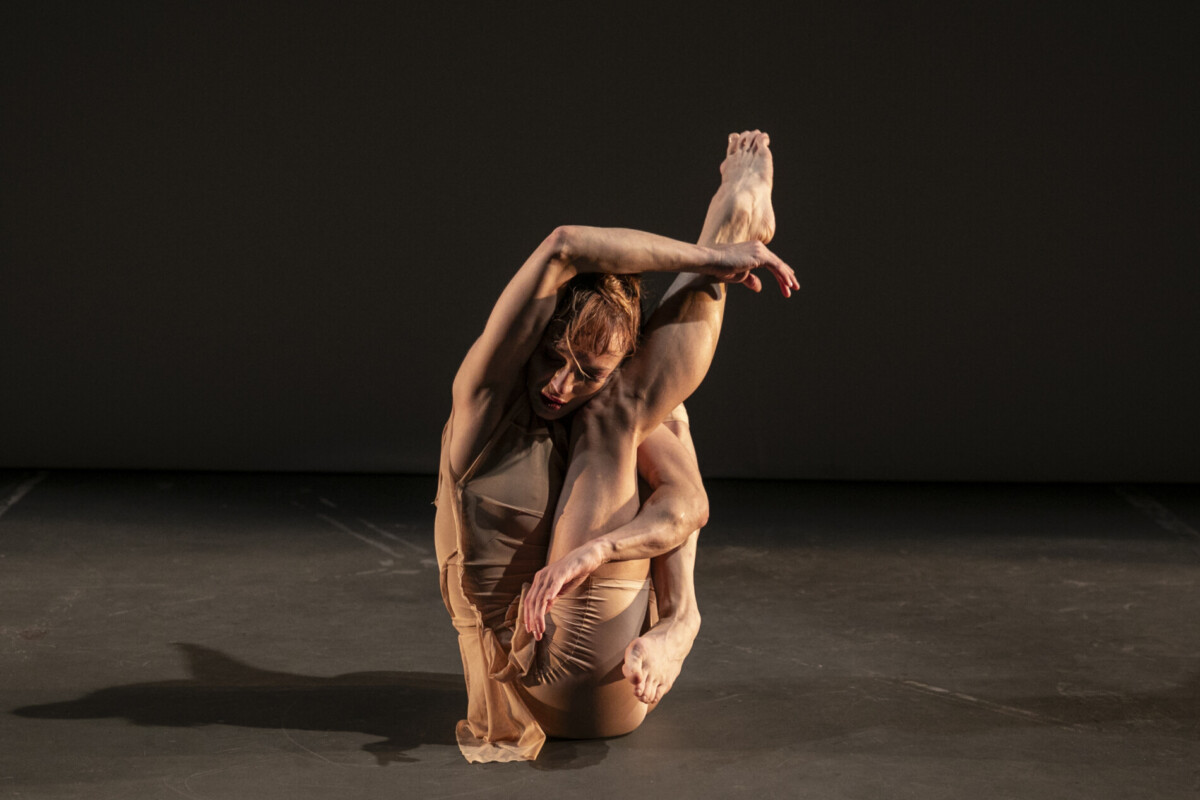

On stage, three solos on the edge of the impossible, at the limit of physical performance, and so interesting -for that very reason- to be thought of from a disciplinary approach that, curiously enough, also seems to strain its own principles. There is something risky and at the same time fascinating about being there in front of Croatto and her dances, as solitary as they are passionate.

Solos Ext3mos (Three Extreme Solos) are three pieces that mix classical ballet, expressionist dance and butoh techniques with multimedia resources. Against this, I believe I own the theoretical tools to face the task of thinking about a complex body which, from the outset, is not presented subtly, far from the figure of the sylph. However, today those tools sound pure slogans to me.

Then, I choose a different path. I turn to Nicolás Rosa’s fascinating text “The nature of passion”[2] from which the almost spontaneous question arises: What moves that body, and I discover that in Solos Ext3mos a body crossed by desire “speaks” to us or, more precisely, I hear the clamour of three bodies affected by three absences.

Solo 1

By way of social criticism, this first section of the presentation consists of the hyperbolic thematization of the female body immersed in a social device which assigns both a role and a rhythm. Different scenes depict sociological stereotypes such as that of a woman who holds her gaze defiantly in front of the public while smoking a cigarette, another one who goes for groceries to the supermarket, or the one who succumbs to the gift-trap of a red rose.

On the sound level, this piece uses repetitions of German words (voiced off as if it were a language course). The costumes consist of all-in-black leather and mesh attire with black ankle boots, in reference to the punk style, in accordance with the visual background by the artist Silke Mansholt, which evokes the graffiti of the Berlin Wall. From these elements which are sustained in a rhythm of unbalanced effect -exacerbated by the loop of certain phonemes-, the body fluctuates through an alternation of agile movements and frenetic walks; thus, constructing an artificial, uncomfortable dance. It is about a tense body, fearful of the possibility of no longer belonging and, for this very reason, it attends to and executes its role with energetic and repeated movements until exhibiting a nervous breakdown or exhaustion. This body twists, shakes and pushes itself to the limit. Long-suffering but always driven by the desire to remain part of it.

Solo 2

This scene begins with a soft instrumental melody that, at first thought, suggests to the viewer that what follows will be of great relief in relation to the intensity experienced a few minutes before.

The black-box stage together with the use of minimal costumes make the light prominent. The dance is performed based on a poem[3] that is heard off and on which the performer performs a lip sync.

yesterday I did a new dance – a dance of fear – small movements – perfectly choreographed – alarm gestures – jolting moves – laboured breathing – it was such – its success – that I will dance it – today again – and tomorrow – and the day after that[4]

The artistic undulation that the movement acquires combined with the surface of the body through subtle games of shadows emphasise the recitation.

The tempo is permanently varying, on which the body produces compulsive movements by thumping and shaking, turning as well as release-and-fall gesturing that produce a sense of helplessness, of being out of control (the unpredictability of these actions causes an anxiety effect). Gradually, the body comes to a halt, becomes small and vanishes.

It is the most subtle and bereft solo of the three, however, it is the one that exhibits an absolutely overwhelmed carnality, lost in sadness and solitude. A body leaning over an abyss, counting on nothing but itself to keep from falling.

Solo 3

It is based on five songs in voice (off) by Elizabeth Woollett with texts by Goethe, which explore the themes of nature, love and loss. The dancer moves accompanied by a martial arts Bo stick.

In this third solo, the body ceases its subjectivity to become pure materiality subsumed under the pulsed movement and the extensive gesture. As a partner, a long wooden cane is added to the scene, which collaborates as a pendulum needle with the mimesis of a metronome; its base is the performer herself positioned vertically, or rather it could be a spear used by the dancer to repeatedly address the spectators. In this way, bringing them to the unwavering rhythm of the time that marks her movements. From a body point, attached to a regular tempo, to a body trajectory (aspects aligned by the paintings that serve as a backdrop[5] ). A body that at times extends itself through the object to focus on the figurative effects of a personal space projected towards the extrapersonal. In this third solo, we observe a present body that interrogates, challenges and strains itself within its own limits but in search of something beyond.

On Balance

The variations in the movement and posture tone, appearing at times whimsical and extravagant, modulate three distinctive emotional moods in complement or counterpoint with the verbal expression together with the sound and visual element.

The Cowie-Croatto duo wields (there is no better term) some physicality that links the social and the individual figuratively. The act becomes distinctive by varying in its typification, which oscillates between presenting itself as a mirror of instincts or as pure physiognomy.

Then, what could be said from a semiotic point of view? Well, that we are dealing with three solos, or rather, with one body and three ways of being affected. Three variations in dance that allude to an embodied emotion which takes shape in lacking states. Where the absent subdues but also mobilises, leading to linger on in resistance.

In short, and from the position of expectation, three ways of being impressed and transformed. Three passions.

***

Notes

[1] From the rediscovery of the body by Semiotics in the last decades of the twentieth century to the present day, about forty years have passed. The main research currents have positioned themselves, at a greater or lesser distance, from what Nicolás Rosa (2005) called “A general theory of emotions” with long philosophical, psychoanalytical and aesthetic roots, such as the Semiotics of Passions by Greimas and Fontanille (1991), or the studies on referentiality and perceptual judgments developed by Humberto Eco (1997) present different descriptive aspects with a phenomenological-structural tendency in the way they have constructed the body as an object of analysis and theorisation. In recent years, the queries that have emerged in the light of studies focused on materiality refer to the place of embodied memory; the functioning of perception as a multidimensional interface as well as the status of the body and its artification within the framework of mediatisation.

[2] The Nature of Passion (2016). Digital Studies, 17, 35-49. https://doi.org/10.31050/re.v0i17.13496.

[3] Authored by Billy Cowie.

[4] First stanza of the poem “De lo Alto de Altos Edificios” (“From the Top of Tall Buildings”) (2020).

[5] Also by Silke Mansholt.

First photo @lurivero.ph

Mientras asistía a esta performance venían a mi mente varias afirmaciones que podrían hacer de antesala a la construcción de una semiótica del cuerpo[1]. En escena, tres solos al borde de lo imposible, al límite de la realización física, y tan interesantes -por eso mismo- de ser pensados desde un enfoque disciplinar que, curiosamente, también parece tensar sus propios principios. Hay algo riesgoso y a la vez fascinante de estar ahí frente a Croatto y sus danzas, tan solitarias como apasionadas.

Solos Extr3mos se trata de tres piezas que mixturan técnicas del ballet clásico, de la danza expresionista y del butoh con recursos multimediales. Frente a ésto, creo tener herramientas teóricas para encarar la tarea de pensar en un cuerpo complejo que, ya de primeras, no se presenta de forma sutil, lejos está de la figura de la sílfide. Sin embargo, esas herramientas, hoy, me resuenan a puro slogan.

Entonces, elijo un camino diferente. Recurro al fascinante texto de Nicolás Rosa “La naturaleza de la pasión”[2] a partir del cual surge la pregunta casi espontánea: ¿Qué mueve a ese cuerpo?, y descubro que en Solos Extr3mos nos “habla” un cuerpo atravesado por el deseo o, para ser más precisa, escucho el clamor de tres cuerpos afectados por tres ausencias.

Solo 1

A modo de crítica social, este primer tramo de la presentación consiste en la tematización hiperbólica del cuerpo femenino inmerso en un dispositivo social que le asigna tanto un rol como un ritmo. En diferentes cuadros se figuran estereotipos sociológicos como, por ejemplo, el de una mujer que sostiene la mirada desafiante frente al público mientras fuma un cigarrillo, otro que va de compras al supermercado, o aquel que sucumbe al regalo-trampa de una rosa roja.

En el plano sonoro, esta pieza utiliza repeticiones de palabras en alemán (expresadas en off a modo de curso de idiomas). El vestuario consiste en un atuendo en cuero y malla y borceguíes, todo en colo negro, en referencia al estilo punk, acorde con el fondo visual de la artista Silke Mansholt, que evoca los grafitis del Muro de Berlín). A partir de estos elementos y sostenido en un ritmo de efecto desequilibrado – acentuado por el loop de ciertos fonemas -, el cuerpo oscila a través de una alternancia de movimientos ágiles y de caminatas frenéticas construyendo una danza artificial, incómoda. Se trata de un cuerpo tenso, temeroso ante la posibilidad de dejar de pertenecer y, por eso mismo, atiende y ejecuta su rol con movimientos enérgicos y repetidos hasta la crisis nerviosa o la extenuación. Se retuerce, se sacude, se coloca a sí mismo al límite. Sufriente pero siempre impulsado por el deseo de seguir siendo parte.

Solo 2

Esta escena inicia con una suave melodía instrumental que, en una primera impresión, sugiere al espectador que lo que sigue será de gran alivio en relación con la intensidad vivida hace pocos minutos atrás.

El escenario, de caja negra; el vestuario, mínimo por lo que la luz toma el protagonismo. La danza se ejecuta en base a un poema[3] que se escucha en off y sobre el que la performer realiza un lip sync.

ayer hice un nuevo baile – un baile de miedo – pequeños movimientos – perfectamente coreografiados – gestos de alarma – respingos nerviosos – respiración entrecortada – fue tal – su éxito – que lo bailaré – hoy de nuevo – y mañana – y el día después [4]

La ondulación plástica que adquieren el movimiento y la superficie del cuerpo mediante juegos sutiles de sombras acentúa lo recitado.

El tempo va variando permanentemente y, sobre este plano, el cuerpo produce movimientos compulsivos como golpeteos y sacudidas, giros y gestos de soltar y caer que producen una sensación de impotencia, de estar fuera de control (la imprevisibilidad de estas acciones promueve un efecto de ansiedad). Progresivamente el cuerpo se detiene, se hace pequeño y desaparece.

Se trata del solo más sutil y despojado de los tres, sin embargo, es el que exhibe una carnalidad absolutamente agobiada, perdida en la tristeza y la soledad. Un cuerpo asomado a un abismo que no cuenta con nada más que sí mismo para no caer.

Solo 3

Esta parte se basa en cinco canciones en voz (en off) de Elizabeth Woollett con textos de Goethe que exploran los temas de la naturaleza, el amor y la pérdida. La bailarina se mueve acompañada de un palo Bo de artes marciales.

En este tercer solo el cuerpo deja de su subjetividad para ser pura materialidad subsumida al movimiento pulsado y al gesto extensivo. Como partenaire se suma a la escena el largo bastón de madera que colabora a modo de aguja pendular con la mímesis de un metrónomo y cuya base es la propia performer situada en posición vertical (o bien podría ser una lanza mediante la que la bailarina interpela de forma repetida a los espectadores trayéndolos al ritmo inquebrantable del tiempo que signa sus movimientos). De un cuerpo-punto, apegado a un tempo regular, a un cuerpo-trayectoria (aspectos homologados por las pinturas que hacen las veces de telón de fondo [5]). Un cuerpo que por momentos se extiende a través del objeto para centrarse en los efectos figurativos de un espacio personal que se proyecta hacia lo extrapersonal. En este tercer solo observamos un cuerpo presente que se interpela, se desafía y tensa hacia sus propios límites pero en busca de algo más allá de sí mismo.

Balance

Las variaciones de tonicidad del movimiento y de posturas, que por momentos aparecen como caprichosas y extravagantes, en complemento o contrapunto con la expresión verbal y el elemento sonoro y visual, modulan tres climas emocionales distintivos.

La dupla Cowie-Croatto empuña (no hay otro adjetivo mejor) una corporalidad en donde se enlazan figurativamente lo social con lo individual, la singularidad del acto con lo plural de la tipificación y que oscila entre presentarse como espejo de los instintos o como pura fisonomía.

Y entonces, ¿qué queda por decir desde una mirada semiótica? Pues que se trata de tres solos, o mejor dicho, de un cuerpo y tres maneras de ser afectado. Tres variaciones en las que la danza alude a una afectividad que se encarna y toma forma en estados de carencia. Donde lo ausente somete pero también moviliza, llevando a persistir en la resistencia.

En definitiva, y desde la posición de expectación, tres formas de ser impresionado y transformado. Tres pasiones.

***

Notas

[1] Desde el redescubrimiento del cuerpo por parte de la Semiótica en las últimas décadas del siglo XX, han transcurrido alrededor de cuarenta años. Las principales corrientes de investigación que se posicionaron a mayor o menor distancia respecto de lo que Nicolás Rosa (2005) denominó “Una teoría general de las emociones”- de larga raigambre filosófica, psicoanalítica y estética-, tales como la Semiótica de las pasiones de Greimas y Fontanille (1991) o los estudios sobre la referencialidad y los juicios perceptivos desarrollado por Humberto Eco (1997), presentan diferentes aspectos descriptivos con tendencia fenomenológico-estructural en el modo en que han construido al cuerpo como objeto de análisis y de teorización. En los últimos años, los interrogantes que emergen a la luz de los estudios con foco en la materialidad refieren al lugar de la memoria encarnada, al funcionamiento de la percepción en tanto interfaz multidimensional y al estatuto del cuerpo y su artificación en el marco de la mediatización.

[2] La naturaleza de la pasión. (2016). Estudios Digital, 17, 35-49. https://doi.org/10.31050/re.v0i17.13496

[3] Autoría de Billy Cowie.

[4] Primera estrofa del poema De lo Alto de Altos Edificios (2020).

[5] También de de Silke Mansholt.

Foto principal de esta crítica: @lurivero.ph