A review of recent short film releases

–Frontiers (Eve McConnachie)

–Etch (Abby Warrilow & Lewis Gourlay)

–Lace (Roberta Jean)

–There not There (Penny Chivas & Paul Michael Henry).

The recent success of the Screen.Dance festival in Perth in May this year and the international attention it gained, has nudged me to write a little about some recent short dance on screen works produced in Scotland and putting them in some critical and international context.

Screendance coming out of Scotland today while relatively successful to its small size, is limited and the successes in film festivals have been down a small number of artists. This is slowly changing, partly due to the funding from Creative Scotland and arts organisations here becoming more open to supporting this genre of work. But also, in part, due to a new serious intention from artists to explore the interfaces of choreography and cinema, and a recognition of the possibilities to present work internationally and develop a new type choreographic voice.

There are a many reasons for excitement about the future of screendance in Scotland just now with several recent film releases that use diverse interdisciplinary approaches. Artists such as Eve McConnachie, Roberta Jean, Abby Warrilow and Lewis Gourlay, Penny Chivas and Paul Micheal Henry show the range of what can be done with this genre. With an international festival and a growing screendance collection at Horsecross in Perth, the state of the art is in good form here.

In screendance as in most art there is a conceit in these works that we accept. The conceit that normal rules don’t apply. Take away the music score from most cinematic works and the emotional impact is diminished. Take away the music from a music video and people are behaving weirdly. We accept the invisible guiding hand of the director, composer, editor, digital effects artist, to propel us into an alternate reality.

Such is Screendance. How to make an audience believe in the dance? Artists and film makers hope an audience will be drawn into a space and place, and transported through a new world and, on arriving at the closing credits, feel a little changed with no words needed to explain.

Accepting the artistic vision.

What makes a “good “ screendance? What defines this incredibly diverse and evolving hybrid genre of artists moving image? The first part of any definition should perhaps be that the film could not be reproduced exactly live, on stage or on location. The second should then be that there is a choreographic sensibility infusing both the dance and cinematic elements. The motion of the performer, camera along with the sound and edit are fused in the service of one compositional and choreographic idea. Of course there are enough people, academics and artists, with their own perspectives on this but I think these two definitions cover the core of what truly hybrid Screendance artists do. I am certainly placing the four screendance works from Scotland reviewed here in this frame and the wider international context.

Frontiers

Eve McConnachie is an in house graphic designer and film maker for Scottish Ballet. From this incredibly enviable and privileged position she has carved out a role crafting several high quality screendances. McConnachie has strong sense of visual composition and screen space reflecting her background in design. This aesthetic has served her well when it comes to collaborating with dance artists. Three years ago she won awards with “Maze” her quirky, rhythmical and geometric investigation of Govanhill swimming baths in Glasgow through a duet. This was quickly followed by the less successful but sensitively made collaboration with poet Jackie Kay and artistic director Christopher Hampson “Haud me Close”. Her new work choreographed by San Francisco Ballet dancer Myles Thatcher “Frontiers”, was created for the recent Scottish Ballet Digital Season and is said to examine gender norms inherent in classical ballet. The setting is under a motorway flyover giving the work a gritty urban feel. The virtuosic technicalities of the dancers solos are cut seamlessly through match frame cutting. In this way it appears one dancer merges into another. The music drives the work forward and the effect is energetic and absorbing. If I was going to be critical I would say that McConnachie’s work often suffers from falling back on well worn screendance tropes, particularly when it comes to choice of location. I could programme a good hour of works set under flyovers, and another two hours of work using match frame cutting. US director Mitchell Rose alone is the master of match frame cutting and has made a full programme’s worth of such films. Likewise with Maze and Hard me Close, There is at least an hour’s worth of screendance set in swimming pools and a festival’s worth of duets set in abandoned and derelict buildings. However, McConnachie makes work that is highly crafted and beautiful to watch so perhaps we can forgive her these explorations. What I don’t understand is why she chooses to avoid using diegetic sound in her works given the resources at her disposal. Without location sound the works can feel like music videos or fashion commercials, rather than a multi sensory staging that can give dance a cinematic grounding and a hybrid screendance voice.

You can watch here:

Etch

‘Etch,’ is a recent Creative Scotland funded screendance work by long time collaborative partners Abby Warrilow and co-director Lewis Gourlay. It features a solo performance by dance artist Joanne Pirrie and the synopsis describes the film as well as I could.

“A girl hikes across remote moorland. On a hill in the distance, stands a lone building, which she discovers is a long abandoned school hall. An upright piano sits in the far corner. She takes off her muddy boots and with confidence in her gait, strides across to the piano and pulls it by one corner. The rusted wheels are jammed and it pivots, creating an arc. A line is carved in layers of compacted dust and the ancient wooden floor splinters with the weight of the instrument. In the centre of the room, hinged on one foot, she extends her leg and rotates swiftly and with graceful power. “

Abby and Lewis run a production company, Cagoule, that makes commercials, music videos and online content. Their combined skills shine through this work. Lewis has a background in post production working as an editor, motion graphic and vfx artist; Abby is a director and choreographer. In amongst gaining a string of international film festival laurels, the film recently picked up an award for best UK film at Screen.Dance -Scotland’s Festival of Dance on Screen in Perth this year and two award nominations in Japan for best dancer and best cinematography.

A work that is part cinematic narrative, part dance performance, part music video, and part animation ‘Etch’ is a screendance that creates a truly hybrid choreographic and cinematic world. The production skills honed over years of experience in the commercial and arts sector are clearly on display here. The camera choreography and edit flow well with the sound score and the dubbing mix with the live sound is perfect. The fact that it is set in an old abandoned building is set up well in the narrative and gives the premise a natural context. I’ve heard from other critics that the promise at the start of the dance doesn’t quite deliver at the punchline but for me I’m still captivated by the visual FX and the unfolding of the work.

The trailer can be seen here:

Lace

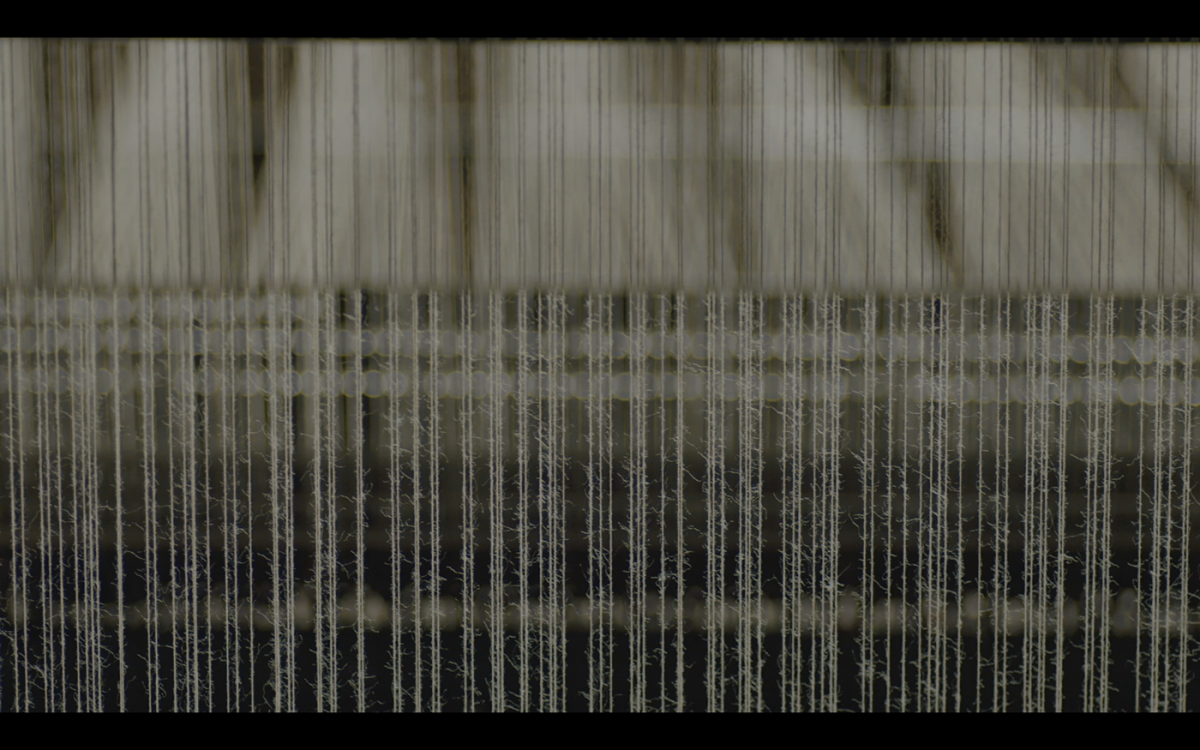

The opening shots of this work by Roberta Jean show where her heart appears to lie as much in the world of artist’s moving image as screendance. Close ups of threads and machine parts and hair in soft focus and fine detail with a gentle pulsing sound track are suddenly interrupted by a surge of machine noise. And the work evolves as much as a visual study, an audio art work as a choreographic one. This film is set in an old lace factory in the west of Scotland and has echoes of the Charlie Chaplin film ‘Modern Times” where the performers mimic and contrast the movements and rhythms of the machinery?. Are the dancers choreographed by the machines or enslaved by their production imperative? That something so intricate and refined is created out of such brute force is a wonder. I am drawn back to this work to try and unpick its intent and get a feel for its weft and weave.

Lace is part of a sequence of three films, together forming a screen version of Jean’s critically acclaimed live work Brocade. Lace was funded by Creative Scotland and shot on location at MYB Textiles in Ayrshire, the only producer in the world to still manufacture patterned lace with original looms. Described by the artist “Movement and sound are propelled along a catwalk and sonic textures resonate with the presence of women forging alliances.”

Roberta Jean has an original voice in this world and if it feels sometimes fragile and tentative it is equally rich and brave. How it will be received in screendance festivals I don’t know, but I hope there are platforms for Lace at galleries and film festivals out of the dance sector. This work has a depth and sensitivity to it that is missing in many of the films that I am asked to review but the lack of a sense of structure and trajectory might put curators of film festivals off selecting.

Lace is available to watch here:

There not There

By far the lowest budget approach of the four works reviewed here. ‘There not There’ shows what can be done with minimal resources for maximum atmosphere. This collaboration between artists Paul Michael Henry and Penny Chivas draws on their dance improvisation and Butoh experience. That this screendance has a certain production naivety to it should not distract from its heartfelt exploration of space and place. The film reveals the artists performing individually in forest locations, watery reed beds and an old boat house. It never feels contrived or over played and there is connection created to character. The understated gestures and movements and occasional soft focus camera work, gently guides us through this work with an ambient music score to support the intensity. I miss any reference to the sound of the location or the artists interaction with water and leaves. Why do dance artists not like to mix sound into their works? Is it forgotten? Are they so used to watching music videos that they forget that cinema has an audio dimension? In any case this work would be so much richer if you could hear the sounds of the dancers in their environment. This work sometimes feels like documenting dancing in a place as opposed a truly hybrid work where camera and sound and edit are fused and infused with choreographic intent. Again some of the action I feel I have seen before in many other works, for example the image of a dancer curling up in a pile of leaves is something screendance artists have used for decades.

I don’t want to be too critical of this film as it is as much a research process for the artists as anything and taking my curatorial hat off the work still engages me in an emotional way. The work could absolutely be shown in the context of artist moving image and I hope they continue to develop their practice in screendance as they have great potential to develop an original voice in the genre.

Contact the artists for a preview of this work.

If there is anything I would offer from reviewing this crop of screendance and considering the current state of the art here in Scotland it is there still needs to be a greater awareness of the history of this art form . Art schools teach art history to help develop original voices and university choreography courses likewise. We stand on the shoulders of giants. I am often asked what advice I would give people wanting to make screendance? Some would offer advice technical skills and equipment. I say watch older work. Only then can you have perspective and context for what you are about to make. There are thousands of films out there to see. Go to festivals, search on the web, ask artists to show what they have done. Maybe after that you will avoid some of the traps and tropes that regularly appear in work by newer artists.

For now I feel positive about the direction of travel and the film makers reviewed here should be justifiably proud of their work. It measures up well against the current range of international screendance.

The next big step is to develop a wider audience.

Principal image credits: Still from Lace by Roberta Jean.

Download this article in pdf format: