Witnessing Dance

Mediation and the Technologies of Representation*

It is my intent today to be unashamedly utopian, to address how we look at, how we discuss, how we circulate and inscribe images of dancing bodies in a pluralistic world, a world that is increasingly mediated by technologies of representation, by social media, and by numerous interfaces that distance us from primary, real time experiences of humanness. I will talk about dance in a relational framework, situating dance within a larger conversation, as a discipline within a system of discourse, signifiers and conversations. These are conversations about mark-making, about presence and about bearing witness to a particular kind of humanness that places itself somewhere on the spectrum from sacred to profane. This humanness is performative and has the potential to speak about both democracy and egalitarianism as it both conforms to and reforms the esthetics of contemporary culture. It is a particular kind of humanness that presents its desires, and that often performs desire; that subverts or inscribes desire; and that states such desires in a way that is part of a new paradigm: one that is caught between the modern world and the end of art. In a pluralistic world, dance is a subset of a larger art world. And for today, I would like to ask, “What if?”. What if we leave behind the grinding economic and quotidian demands of a career in the arts and fanaticize about the possibilities of art? What if, for today, we think about art not as entertainment but rather as something sacred? A kind of agreement or social contract in which we agree to allow ourselves to be touched, to have our hearts opened to the gracious gifts of the creative spirit? What if art were a gift, an offering of hope, of love and of transcendence?

What does it mean to be utopian? To be idealistic? To believe that art and art practice does not simply add value to life, but actually has the potential to alter the human landscape; to make human-ness a sustainable, creative endeavor? These questions seem overwhelming. To be such a utopic idealist may mean that one’s expectations are often undermined by the realities of contemporary life and that, at times, the desire for transcendent creative experiences may be met with less than transcendent outcomes. It may mean exquisite failure. However, it also means that at times, when the numerous possibilities for failure are overcome in some mysterious way, transcendence does indeed occur: the spectator is moved beyond words and the alchemy of creativity produces a momentary portal through which pours a kind of divine connectedness. I think these moments actually occur more than we imagine but they are contingent on our ability to be present and mindful enough to acknowledge them and to make space for them in our lives. I am mindful of the fact that much of what I am describing is relational and contextual: that the viewer brings a certain amount of data to each engagement and that if that data synthesizes with the data of a performance or a painting or a piece of music, there may occur a kind of synergy. Artists gestate and birth countless creative gestures, at times without consideration for their eventual reception by spectators or viewers. However, when an artist begins the creative endeavor with a sense of absolute purpose and with intentionality, the interface between public exhibition and private practice often carries a particular sense of clarity. When artists are truly present in the truthfulness of their work, our interface with that work can seem to be a most intimate encounter.

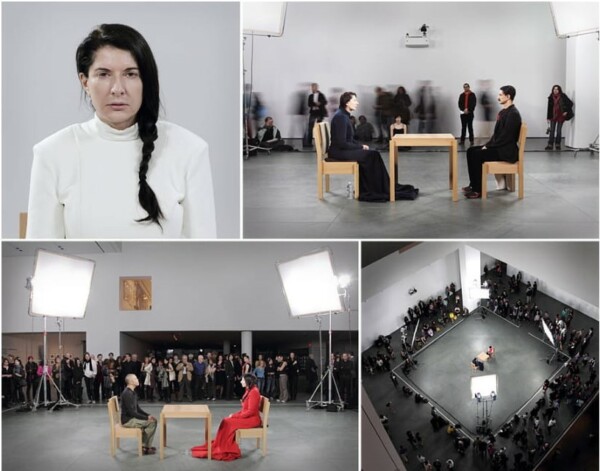

In Marina Abramovic’s recently completed three-month performance at MOMA New York, the artist was quite literally present in the museum, continuously, all day, every day that the museum was open for a period of three months. In this case the artist was present in a prescribed physical location, where she could be found easily by anyone wishing to sit quietly with her in public communion. Abramovic literally carved out a space in her life and in the life of the museum to be present with people whom she did not know or have any previous relationship with. However, she did this in public space in the presence and gaze of an ever-changing community of witnesses. In this project, Abramovic opened her practice to the possibility of absolute failure. What if she could not complete the grueling three-month commitment? What if she became bored or no one showed up to sit with her? What if the people who came were not the people she imagined? Abramovic sat, available and present for each participant, eyes dropping at the end of one encounter, her consciousness cleansed prior to the next, day after day after day. What occurred in these encounters, which began and ended at the decision of the participant, was at times evocative, transformational, and emotionally charged. At other times it was, I am sure, profoundly pedestrian. But taken as a whole, the intent of this work and indeed its ultimate realization was a kind of blessing. What does it mean to be so present, so available? It was a work that most certainly tested the limits of Abramovic’s commitment to a durational, social art practice. And viewers clearly projected their desires onto both the artist and the whole of the work as well.

However, the clarity of the vision to create, as she calls it, a “charismatic space,” overwhelmed any external pressures that may have compromised such a vision. In the work that resulted from her artistic generosity, Abramovic created a sacred space within the constructs of a public art museum, blurring the boundaries of spectator and participant, artist and public. In the generous atmosphere of The Artist is Present, concerns extraneous to Abramovic’s intentionality evaporated, allowing the viewer an empathic interface with the artist, one that was a product of esthetic and ethical choices and one that was not separate from the work but was indeed contingent on and synergistic to it. But when we think of interface generally (in the contemporary world), we think about digital culture.

Just as raw materials do not become technology without engineering, technology alone (digital culture) cannot effect change; social or cultural change does not occur in a vacuum. It is the application of creativity to technology and of technology to creative impulses that often initiates seismic paradigm shifts.

Digital technology allows us to see more clearly; it can extend and amplify the optics of vision in such instruments as the telescope and microscope. Cameras and screen-based technologies also extend the possibilities of vision and do so as they record, re-record, stream, playback, distribute and archive performance of all kinds. Dance has long relied on such technologies as a kind of forensic proof if its own existence. As a culture we tend to trust pictures more than memory, moving images over storytelling, and mediation over live experience. Media and the technologies of representation and distribution are valuable tools for dance artists; these tools are the means by which culture circulates beyond live performance. I have written about my desires for a kind of media that is pristine and clear, that is a representation of bodies and of performance that is of the highest definition and that exhibits a mastery of technique and virtuosic ability. But I also realize that such a desire precludes the possibility of a truly democratic use of media. I am torn between the pull of an often-hierarchical use of media as a way to mediate and circulate performance, and one that is more egalitarian.

The artist and writer Hito Steyerl proposes what she calls a “poor image”: one that, as it is circulated through the internet and through the diaspora of digital visual culture, proudly bears the marks of such a journey as a kind of homage to its own wanderings. She says:

The poor image is a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard. As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.[1]

Digital culture is open source culture; it denies and rejects authorship. To commit a record of one’s work choreographic work to the digital world (either as an archive or as a screendance) is to tacitly acknowledge that ownership of ideas and creative capital is moot, that creativity is a global collaboration. We can liken the process of uploading and linking URLs, blogging and YouTubing to a kind of digitography: gesturing or writing in digital space.

As digital citizens in the twenty-first century we are the inheritors of Roland Barthes’s prophetic description of the death of the author in Image, Music, Text, from 1977: “Writing is that neutral, composite, oblique space where our subject slips away, the negative where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity of the body writing” (pg. 142). Barthes suggests that public writing, or writing made public, enters the collective consciousness and becomes errant and diasporic to the point that ownership of the generative idea and the provenance of its originator are not only irrelevant but largely made absent. He made this claim in an era that predated the internet and digital culture. He was speaking about books, texts, and the products of analog cultural production. However, it is apropos of contemporary culture and our immersion in digital communication and representation. How we think about ownership and authorship is part of an evolving definition of what it means to be an artist in the digital world. It is part of a new definition of artistic citizenship and requires us to be a part of a new discourse and a new dialog that, while building on older historical models, must also break with traditions that are no longer functional.

To be a digital citizen and an artist engaged with digital technologies in a pluralistic culture is neither a promise of creative communication nor a guarantee of social fracturing and isolation. It is however, a challenge. To be “connected” digitally and to be connected in the fleshy, corporeal way that suggests an embrace or an enveloping may require some negotiation. It certainly will require intentionality. The overwhelming appetite of digital culture and the corresponding burden of being a participant in it tends to wither the resolve of even the most technologically facile among us. It simply takes an unreasonable amount of time to tend to all the screen-based requirements of daily life. As the boundaries of digital life and art facilitated by digital culture have seemingly dissolved, how do we separate the two? How do we create visual distance between pedestrian digital communication and maintenance of daily life and career from our distinct creative projects that take advantage of similar technologies? Perhaps an answer lies in thinking again about the nature of interface, of prosopon, one face facing another. There is beauty in difference, in the reflective moments that art in its most basic function can provide. To be reflective is to both ponder one’s existence and purpose and also to mirror the world as it is. Reflection is made possible by the most basic of technologies, a still smooth surface, an interface that both receives and responds to our projections and our desire to be seen, to be witnessed. Perhaps that is the purpose of art: to reflect and to create spaces for reflection. Perhaps dance, in an ideal world, freed from the weight of commerce and the marketplace, fulfills a similar purpose both for the artist and for the viewer as well.

*Excerpt from Keynote Talk presented at the Canadian Dance Assembly Conference, 22 October 2012.

[1]“In Defense of the Poor Image”. http://www.postmedialab.org/defense-poor-image.

Cover photo: Still from Circling, film by Douglas Rosenberg with Sally Gross.

Atestiguando la Danza

Mediación y Tecnologías de la representación*

Es mi intención hoy ser desvergonzadamente utópico, referirme a cómo miramos, cómo discutimos, cómo hacemos circular e inscribimos imágenes de cuerpos danzantes en un mundo pluralista, un mundo que, cada vez más, está mediado por las tecnologías de la representación, por las redes sociales y por numerosas interfaces que nos distancian de las experiencias primarias y en tiempo real de lo humano. Hablaré sobre la danza en un marco relacional, situándola en una discusión más amplia, como disciplina dentro de un sistema discursivo, de significantes y conversaciones. Éstas son conversaciones sobre dejar una marca, sobre la presencia y sobre sostener un testimonio de una clase particular de humanidad que se coloca en algún lugar del espectro entre lo sagrado y lo profano. Esta humanidad es performática y tiene el potencial de hablar tanto de la democracia como del igualitarismo, como si ambos conformaran y reformaran la estética de la cultura contemporánea. Es un tipo particular de humanidad que expone sus deseos y que, muchas veces, los realiza. Que subvierte o inscribe el deseo y que lo declara como parte de un nuevo paradigma: un paradigma que queda atrapado entre el mundo moderno y el fin del arte. En un mundo pluralista, la danza es un subconjunto del más amplio mundo del arte. Y, por hoy, me gustaría preguntar: “¿Qué pasaría si…?”. ¿Qué pasaría si dejáramos atrás las demoledoras demandas económicas y cotidianas de una carrera de artes y fantaseáramos acerca de las posibilidades del arte? ¿Qué tal si, por hoy, pensáramos en el arte no como entretenimiento sino más bien como algo sagrado, un tipo de pacto o contrato social en el cual nos pusiéramos de acuerdo en permitir ser tocados, en abrir nuestros corazones a los graciosos dones del espíritu creativo? ¿Qué tal si el arte fuera un don, una ofrenda de esperanza, de amor y de transcendencia?

¿Qué significa ser utópico? ¿Ser idealista? ¿Creer que el arte y la práctica artística no simplemente suman un valor a la vida, sino que realmente tienen el potencial de alterar el paisaje humano, de hacer que lo humano sea un emprendimiento sustentable y creativo? Estas preguntas parecen abrumadoras. Ser un idealista tan utópico puede significar que las expectativas de uno a menudo se vean socavadas por las realidades de la vida contemporánea y que, en ocasiones, el deseo de experiencias creativas trascendentes puede encontrarse con resultados poco trascendentes. Puede significar un fracaso exquisito. Sin embargo, también significa que a veces, cuando las numerosas posibilidades de fracaso se ven superadas de algún modo misterioso, la trascendencia, de hecho, ocurre: el espectador es conmovido más allá de las palabras y la alquimia de la creatividad produce un portal momentáneo a través del cual fluye una clase de conectividad divina. Creo que estos momentos en realidad ocurren más de lo que imaginamos, pero dependen de nuestra capacidad de estar presentes y ser lo suficientemente conscientes como para reconocerlos y hacerles espacio en nuestras vidas.

Yo soy consciente del hecho de que mucho de lo que estoy describiendo es relacional y contextual: que el espectador aporta una cierta cantidad de información a cada participación y que si esa información se sintetiza con la de una performance, una pintura o una pieza de música puede ocurrir una especie de sinergia. Los artistas gestan y paren incontables gestos creativos, a veces sin consideración por su eventual recepción por parte de los espectadores. Sin embargo, cuando un artista comienza una aventura creativa con un sentido de propósito absoluto y con intencionalidad, la interface entre la exhibición pública y la práctica privada a menudo conlleva un particular sentido de claridad. Cuando los artistas están verdaderamente presentes en la veracidad de su trabajo, nuestra interface con esa obra se puede apreciar como un encuentro más íntimo.

En la actuación de tres meses de duración de Marina Abramovic, recientemente completada en el MOMA de Nueva York, la artista estuvo, literalmente, presente en el museo de manera continua, todo el día, todos los días que el museo estuvo abierto por un período de tres meses. En este caso, en una locación física prescripta, donde podía ser encontrada fácilmente por cualquier persona que quisiera sentarse con ella en silencio en comunión pública. Abramovic literalmente esculpió un espacio en su vida y en la vida del museo para estar con gente a quien no conocía y con quien no tenía ninguna relación previa. Sin embargo, lo hizo en un espacio público ante la presencia y la mirada de una comunidad de testigos en constante cambio.

En este proyecto, Abramovic abrió su práctica a la posibilidad de un fracaso absoluto. ¿Qué hubiera pasado si no conseguía completar el compromiso agotador de tres meses? ¿Qué tal si se hubiera aburrido o nadie hubiera ido a sentarse con ella? ¿Qué tal si la gente que acudía no hubiera sido la que ella se imaginaba? Abramovic se sentó, disponible y presente para cada participante, bajando sus ojos al final de cada encuentro, lavando su conciencia antes del próximo, día tras día. Lo que ocurrió en estos encuentros, que comenzaban y terminaban por la decisión de cada participante, fue, a veces, evocativo, transformacional y cargado emocionalmente. Otras veces fue, estoy seguro, profundamente pedestre. Pero tomado en conjunto, la intención de esta obra y, de hecho, su realización final fue una especie de bendición. ¿Qué significa estar tan presente, tan disponible? Fue una obra que definitivamente puso a prueba los límites del compromiso de Abramovic con una práctica artística duracional y social. Y los espectadores claramente proyectaron sus deseos sobre la artista y también sobre la obra como un todo.

Sin embargo, la claridad de la visión para crear, como ella lo llama, un “espacio carismático,” desbordó cualquier presión externa que pudiera haber comprometido aquella visión. En la obra que resultó de su generosidad artística, creó un espacio sagrado en medio de la estructura de un museo público, borrando las barreras entre espectador y participante, artista y público. En la generosa atmósfera de The Artist is Present (La artista está presente), las preocupaciones externas a la intencionalidad de Abramovic se evaporaron, permitiendo al espectador una interface empática con la artista, que fue producto de elecciones estéticas y éticas, que no estuvo separada de la obra sino, en cambio, definitivamente dependiente y en sinergia con ella. Pero cuando pensamos en interface. generalmente (en el mundo contemporáneo) pensamos en cultura digital. Así como las materias primas no se convierten en tecnología sin ingeniería, la tecnología por sí sola (la cultura digital) no puede efectuar un cambio; el cambio social o cultural no ocurre en el vacío. Es la aplicación de la creatividad a la tecnología y de la tecnología a los impulsos creativos lo que, a menudo, inicia cambios sísmicos de paradigma.

La tecnología digital nos permite ver más claramente, puede extender y amplificar las ópticas de visión con instrumentos tales como el telescopio y el microscopio. Las cámaras y tecnologías de proyección también extienden las posibilidades de visión y lo hacen en la medida en que graban, re-graban y pueden transmitir en directo, reproducir, distribuir y archivar performances de todos tipo. La danza ha confiado en tales tecnologías como una especie de prueba forense de su propia existencia. Como cultura, tendemos a creer en las imágenes más que en la memoria, en las imágenes en movimiento por sobre la narración y en la mediación por sobre la experiencia viva. Los medios y las tecnologías de la representación y la distribución son herramientas valiosas para los artistas de la danza; estas herramientas son los medios por los cuales la cultura circula más allá de la performance en vivo. He escrito acerca de mis deseos de una clase de medios prístinos y claros, que puedan representar con la mayor definición los cuerpos y las performances que exhiban un dominio de la técnica y el virtuosismo. Pero también comprendo que tal deseo impide la posibilidad de un uso verdaderamente democrático de los medios. Me debato entre la atracción hacia un uso, a menudo, jerárquico de los medios como forma de mediar y hacer circular la performance y uno que sea más igualitario.

La artista y escritora Hito Steyerl propone lo que denomina “imagen pobre/poor image”: la que, al circular por internet y por la diáspora de la cultura digital visual, orgullosamente carga las marcas de tal viaje como una especie de homenaje a su propio derrotero. Dice:

La imagen pobre es una copia en movimiento. Su calidad es mala, su resolución, por debajo de los estándares. Si se acelera, se deteriora. Es el fantasma de una imagen, una preview, un thumbnail, una idea errante, una imagen itinerante distribuida gratuitamente, exprimida a través de conexiones digitales bajas, comprimida, reproducida, rippeada, remixada, así como copiada y pegada en otros canales de distribución.[1]

La cultura digital es cultura de código abierto: niega y rechaza la autoría. El comprometer un registro de una obra coreográfica al mundo digital (sea como un archivo o como una videodanza/screendance) es reconocer tácitamente que la posesión de las ideas y el capital creativo es cuestionable y que la creatividad es una colaboración global. Podemos comparar el proceso de subir y enlazar en internet URLs, hacer blogs y publicar en YouTube a una clase de digitografía: gesticular o escribir en el espacio digital.

Como ciudadanos digitales del siglo XXI, somos los herederos de la profética descripción de la muerte del autor de Roland Barthes en Image, Music, Text (1977: 142): “Escribir es ese espacio neutral, compuesto, oblicuo en el cual nuestro sujeto se escurre, lo negativo donde toda identidad se pierde, comenzando por la mera identidad del cuerpo que escribe”. Barthes sugiere que la escritura pública, o la escritura hecha pública, entra en la consciencia colectiva y se transforma en errante y diaspórica hasta el punto en el que la posesión de la idea generadora y la procedencia de su creador no solo son irrelevantes, sino que en gran parte están ausentes. Él hizo esta afirmación en una era que precedió a la Internet y la cultura digital. Estaba hablando de libros, textos y de productos de la cultura analógica. Sin embargo, es apropiada también en el marco de la cultura contemporánea y de nuestras modalidades de inmersión en la comunicación y representación digitales. La forma en que pensamos sobre la propiedad y la autoría es parte de una definición en evolución de lo que significa ser un artista en el mundo digital. Es parte de una nueva definición de ciudadanía artística y requiere que seamos parte de un discurso y un nuevo diálogo que, al tiempo que se construye sobre modelos históricos antiguos, debe también romper con tradiciones que ya no son funcionales.

Ser un ciudadano digital y un artista comprometido con las tecnologías digitales en una cultura pluralista no es ni una promesa de comunicación creativa ni una garantía de fractura social y aislamiento. Es, sin embargo, un desafío. Estar “conectados” digitalmente y estar conectados en la forma corpórea, carnal, puede requerir cierta negociación. Ciertamente requerirá intencionalidad. El abrumador apetito de la cultura digital y el correspondiente peso de ser partícipe de ella tiende a debilitar la resolución de lo tecnológicamente más fácil entre nosotros. Simplemente lleva una increíble cantidad de tiempo atender a todos los requerimientos de las pantallas en la vida diaria.

Mientras las fronteras entre la vida digital y el arte, facilitado por la cultura digital, aparentemente, se han disuelto: ¿Cómo las separamos? ¿Cómo creamos una distancia visual entre las comunicaciones digitales pedestres, el mantenimiento de la vida diaria y la carrera y nuestros proyectos creativos originales que aprovechan tecnologías similares? Quizás una respuesta yace en pensar, nuevamente, en la naturaleza de la interface, del prósopon[2], una cara enfrentando a la otra. Hay belleza en la diferencia, en los momentos reflexivos en los que el arte, en su función más básica, puede proveer. Ser reflexivo es tanto ponderar la propia existencia y propósito como espejar el mundo tal cual es. La reflexión se hace posible gracias a la más básica de las tecnologías, una superficie quieta y suave, una interface que tanto recibe como responde a nuestras proyecciones y a nuestro deseo de ser vistos, de ser atestiguados. Quizás ese es el propósito del arte: reflejar y crear espacios para la reflexión. Quizás la danza, en un mundo ideal, liberada del peso del comercio y del mercado, satisface un propósito similar, tanto para el artista como para el espectador.

*Fragmento del discurso principal presentado en la Canadian Dance Assembly Conference, 22 de octubre de 2012.

[1] “In Defense of the Poor Image/En defensa de la imagen pobre”. http://www.postmedialab.org/defense-poor-image.

[2] N. T.: En griego en el original, generalmente traducido al español como “persona”.

Foto portada: still de Circling, película de Douglas Rosenberg con Sally Gross.